In Zimbabwe, possessing identity documents such as birth certificates and national identification cards is more than a formality; it is the gateway to full citizenship. Yet for many, particularly in rural and marginalised communities, the absence of such documents has meant exclusion from education, health care, employment, and even the ability to exercise fundamental rights. The story of 24-year-old Kudzanai Kabanda from Mashonaland West encapsulates the silent struggles faced by thousands who live without an official identity, as well as the transformative power of inclusive public service delivery.

For Kudzanai, the challenge began when her father died in 2019, leaving her without a birth certificate or proof of parentage. This absence of documentation, a seemingly bureaucratic issue, quickly translated into an enduring cycle of exclusion. She could not sit for public examinations, apply for jobs, or access basic services. Each attempt to regularise her status led to further frustration, as offices demanded supporting documents she did not have, sending her into a maze of referrals and dead ends. Such cases reveal a critical flaw in bureaucratic systems: when proof of identity is absent, the state often becomes inaccessible, perpetuating inequality and disenfranchisement.

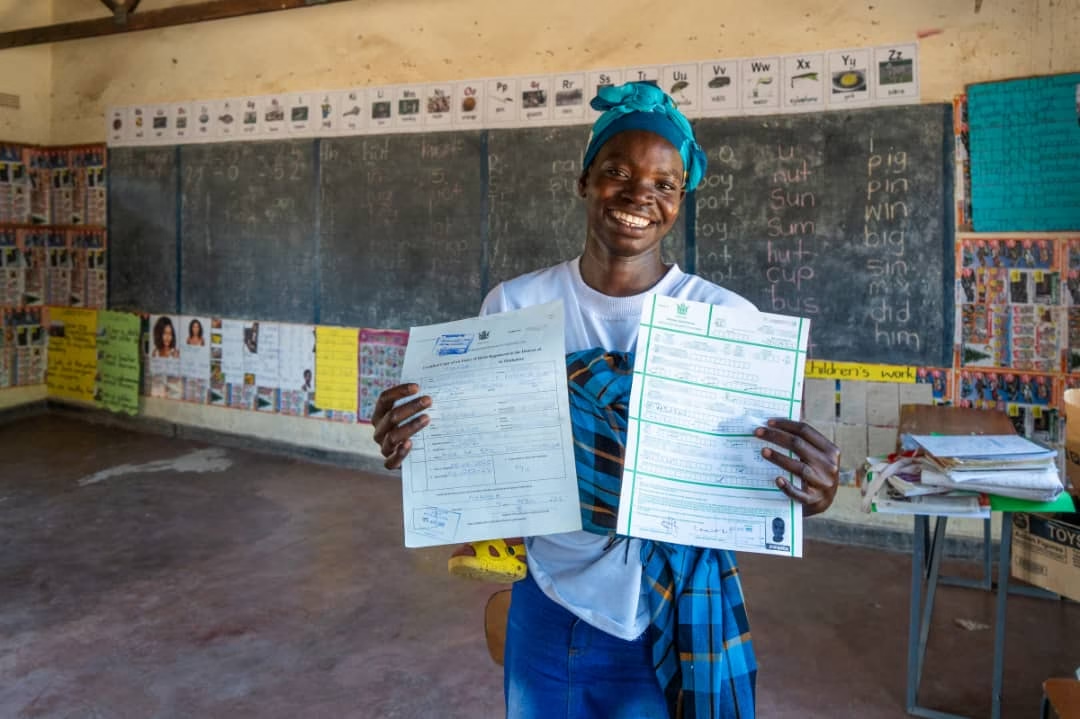

The turning point came with the arrival of a Mobile One Stop Centre, a UNDP-supported initiative that brings essential services into remote areas under one roof. In a makeshift tent erected at a local schoolyard, Kudzanai encountered civil registry officials, health workers, prosecutors, and legal aid providers all working in coordination. Over a span of days, she acquired her father’s death certificate, her own birth certificate, and finally, a national ID card. The relief was not only personal but generational. With an identity card, she could now enrol her child in school, secure employment, and step into a system that had long excluded her.

This single story underscores the systemic challenges Zimbabwe faces in ensuring universal access to identity documentation. Identity is not simply about paperwork; it is tied to dignity, opportunity, and empowerment. The lack of documentation is both a symptom and driver of poverty. When citizens are excluded from formal systems, they become invisible in data, invisible in planning, and invisible in national development. Without reforms, marginalised groups—particularly women, children, and orphans—remain trapped in cycles of vulnerability.

What Kudzanai’s case demonstrates is the effectiveness of integrated, people-centred service delivery. Mobile One Stop Centres simplify complex bureaucracies, reduce travel costs, and provide flexibility by accepting community testimony where official documents are missing. This model not only resolves individual cases but challenges entrenched institutional practices that have long privileged those with resources and connections over the poor and rural. It illustrates how innovation in public administration can bridge long-standing gaps in equity and access.

The broader implication is clear: expanding such mobile interventions could be a decisive step toward inclusive development. National planning, poverty reduction strategies, and social protection programmes cannot succeed if sections of the population remain undocumented. While mobile centres offer an immediate solution, long-term sustainability requires policy adjustments that simplify documentation processes, reduce administrative hurdles, and invest in digital record systems.

For Zimbabwe, the challenge is not only logistical but philosophical. Identity is a right, not a privilege. Ensuring that every citizen has the means to prove their existence is fundamental to building a just society. By breaking the cycle for one young woman, the state and its partners demonstrate that transformation is possible. The task ahead lies in scaling these solutions so that the journey to identity is no longer a struggle but an assured pathway for all citizens