By Aldridge Dzvene

ZESA is no longer just chasing megawatts, it is gambling on a massive new wave of coal fired power to yank Zimbabwe out of rolling blackouts and anchor an ambitious industrialisation drive, even as the world races toward cleaner energy.

Plans outlined to Parliament and regional power stakeholders show that the utility, backed by Government, is pushing an aggressive expansion of thermal generation, centred on Hwange and new private sector plants, while building in solar and battery storage as supporting pillars rather than the main act. The strategy is bold, controversial and defining, because it will determine what powers Zimbabwe’s factories, mines and homes for the next three decades.

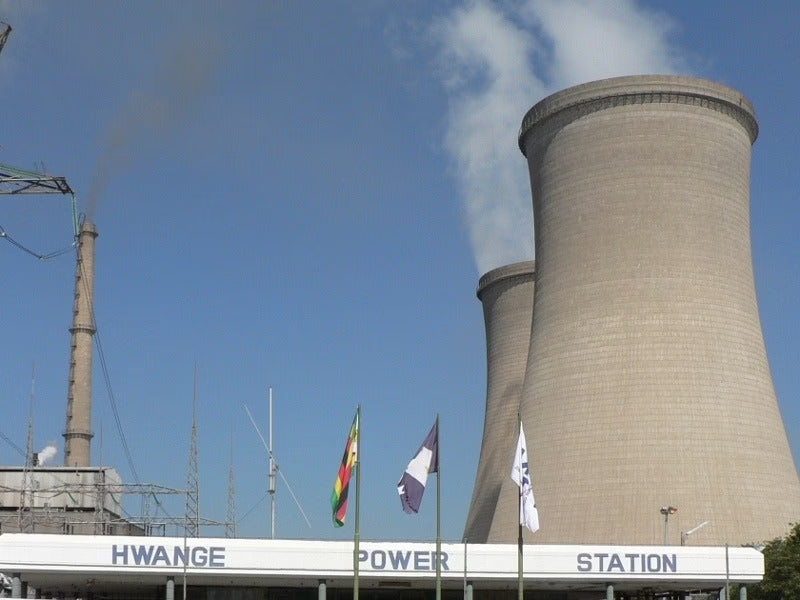

At the heart of the plan is Hwange, the country’s coal fired workhorse. After the commissioning of Units 7 and 8, ZESA now wants additional units and full repowering of the ageing Units 1 to 6 under a proposed US$800 million concession with India’s Jindal group. That deal, once fully approved, is expected to lift generation from the older units from under 500 megawatts to more than 800 megawatts, turning Hwange into a far more reliable baseload station.

In parallel, heavy power users in ferrochrome and steel are developing their own 300 megawatt thermal plant, effectively creating an embedded generation cushion for energy hungry industry and easing pressure on the national grid. For ZESA, that means more room to allocate power to households, farmers and small businesses that have borne the brunt of load shedding.

What makes the current roadmap analytically striking is the way coal is being repositioned, not abandoned. While global narratives lean hard into renewables, Zimbabwe is foregrounding thermal as the backbone, then layering in solar and storage to add flexibility. Utility scale Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) of up to 600 megawatts are planned to soak up excess energy off peak and discharge during the evening surge, smoothing out demand spikes and reducing the severity of power cuts.

From a policy perspective, this is energy realism, not energy romance. The economy is expanding, new mines and refineries are coming on stream, and Vision 2030 targets hinge on dependable power, not promises. ZESA’s thermal heavy path recognises that large scale renewables, grid stability technology and transmission upgrades take time and money which Zimbabwe is still mobilising. In the short to medium term, coal, backed by better technology and tighter environmental controls, is being used as the bridge.

Yet the gamble is unmistakable. Coal projects are capital intensive, long term and increasingly exposed to climate finance headwinds and carbon scrutiny. If implementation is delayed, costs overrun or pollution controls are weak, Zimbabwe risks locking itself into an expensive and controversial power profile just as markets and financiers tilt away from fossil fuels. That is why energy economists are calling for transparent costings, clear decommissioning timelines and an honest integration of renewables rather than token solar fields at the margins.

For ordinary citizens, the stakes are more immediate than global climate debates. Consistent electricity means clinics that do not go dark, irrigation schemes that keep running and SMEs that can plan production without diesel generators draining their profits. For miners and manufacturers, it means the difference between operating at full capacity or being throttled by power cuts.

Ultimately, ZESA’s thermal power expansion is more than an engineering blueprint, it is a statement about how Zimbabwe intends to power growth, manage climate pressure and position itself in a region where neighbours are also scrambling for secure energy. If the mix of coal, solar and storage is executed with discipline, transparency and environmental responsibility, the “thermal gamble” could stabilise the grid and buy time for a deeper renewable transition. If mishandled, it could become an expensive monument to short term fixes.

What is clear is that the country’s energy future is now being written in concrete, steel and coal at Hwange and beyond, and the decisions taken today will echo through Zimbabwe’s economy long after the current load shedding headlines fade.