Zimbabwe is quietly reshaping its regional identity, shifting from a landlocked vulnerability to a land-linked advantage. A wave of mega pipeline investments and port-centric logistics reforms are positioning the country at the heart of Southern Africa’s energy and mineral value chains.

The proposed Beira-Harare-Lusaka oil and gas pipeline, led by Beira Bulk Petroleum Company, the US$48.1 million Deka pipeline upgrade, and President Mnangagwa’s broader Indian Ocean port strategy in Mozambique are interconnected pillars of a deliberate effort to make Zimbabwe a transit, processing, and dispatch hub for fuel, steel, lithium, and bulk commodities serving regional and global markets.

The Beira-Harare-Lusaka multi-grade pipeline, politically endorsed at the inaugural Zimbabwe-Zambia Bi-National Commission and valued at US$1.5 billion, aims to transform Harare from a fuel consumer into a central junction of a regional energy corridor. Once financial closure is reached, the first phase (Mabvuku to Lion’s Den to Lusaka) is expected to be completed within a year, giving Zimbabwe new leverage in northward fuel movement. This would replace thousands of kilometers of costly road transport, allowing Zambia, Malawi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to access fuel via a pipeline through Zimbabwe, while upgrading Harare’s storage and pumping infrastructure.

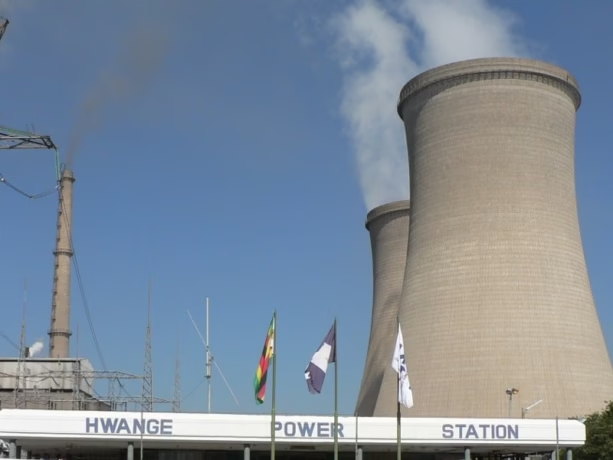

This regional pipeline ambition aligns with the US$48.1 million Deka pipeline upgrade, which addresses the water needs of the Hwange power complex and surrounding communities. By refurbishing the Deka pipeline, Zimbabwe secures reliable water delivery to its thermal power station, supports local industry, stabilizes power generation, and advances its industrialization agenda. Though less prominent than the cross-border pipeline, this upgrade is critical for domestic energy security.

President Mnangagwa’s Vision 2030 and SADC Chairperson role have driven a logistics corridor strategy centered on Mozambican ports (Beira, Maputo, Techobanine, and planned Chongoene facility). As ZANU PF spokesperson Cde Christopher Mutsvangwa notes, Zimbabwe can no longer rely on the 2,000 km route to Durban when shorter routes to the Indian Ocean exist. The emergence of Dinson Iron and Steel Company, lithium investments, and interest in cobalt and nickel flows from Zambia and the DRC underscore the need for port and rail solutions matching industrial growth.

Chongoene, with its rail link, could serve as a gateway for Zimbabwe’s steel and minerals, while upgrades to Maputo and Beira reduce risk and boost capacity. These ports are not just maritime infrastructure—they are the ocean end of a continental logistics network including rail, highways, and pipelines through Zimbabwe. The Beira-Harare-Lusaka pipeline, Deka upgrade, and Masasa pipeline (serving Malawi, Zambia, and Botswana) form part of this integrated system.

The strategy hinges on a simple calculation: controlling the corridor means capturing value. With major steel and lithium projects, the cost and reliability of transporting resources to port will determine competitiveness. Pipelines reduce fuel costs, rail upgrades shorten delivery times, and the Deka upgrade sustains Hwange’s power output. Together, they turn geography into an asset.

Cde Mutsvangwa’s assertion that Zimbabwe is shifting from landlocked to land-linked is more than rhetoric. If executed well, these projects could make Zimbabwe a structural hub in Southern Africa’s growth story. However, success depends on coordination between governments, financiers, and operators. Cost overruns or delays could undermine the benefits. If implemented effectively, the pipelines and port corridors could mark Zimbabwe’s shift from a price-taker to a price-influencing logistics hub.